Pratyaya Deep Bhattacherjee2, Dipanjan Saha2, Soumen Kumar Das2, Ratna Dey3, Malobika Ghosh3, Iti Dutta3, Madan Sarma3, Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya1.

1Consultant, 2Research fellow, 3 Research Assistant. Institute of Pulmocare and Research, Kolkata, India.

Abstract

Background: Treatment of Class III pulmonary hypertension that can affect the oxygenation and quality of life may be worthwhile.

Objective: To identify class III pulmonary hypertension in a tertiary pulmonary OPD practice and observe the effect of treating them with sildenafil on defined indications.

Methods: The presence of pulmonary hypertension was diagnosed on a composite clinico-radio-echocardiographic criteria and the etiological factors were identified using an evaluation algorithm in a referral OPD services. Concomitant to the optimum treatment of their underlying etiological conditions, the WHO functional class III and IV patients from varied etiologies were treated with sildenafil on a real world protocol. The quality of life measured with CAT (COPD assessment test) score, and the resting arterial oxygen saturation were noted at the beginning and after 3 months of sildenafil therapy with documentation of the adverse and serious adverse events.

Results: 81 patients (mean age 62.43±10.17 years) from different etiologies have been recorded to have documented follow up on sildenafil. COPD (35.7%), past history of tuberculosis (21%), indeterminate etiology (13.5%), DPLD (13.5%), and asthma (11%) remain the major causes of pulmonary hypertension. There has been universal improvement across the different causes with the mean CAT score reducing from 15.33±5.52 to 13.01±5.79 (p=0.004) and the mean arterial oxygen saturation improving from 94.6±2.90 to 95.05±3.15 percent. The improvement in CAT was significant for COPD (p=0.03, n=29)

Conclusion: the causes of Class III PH looks different than known and the patients show improvement in quality of life following sildenafil therapy.

KEY WORDS: pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary artery pressure, quality of life, CAT (The Pulmo -Face, 2014; 14:1, 5-9 )

Address of correspondence: Dr. Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya, Institute of Pulmocare and Research, CB-16, Sector-1, Salt Lake, Kolkata- 700 064, India, Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

ABBREVIATIONS:

PH – pulmonary hypertension

OPD – out patient department

PDE5 – phosphodiestyerase-5

QoL – quality of life

COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

DPLD – diffuse parenchymal lung disease

OSA – obstructive sleep apnoea

CAT – COPD assessment test

RHC – right heart catheterization

HRCT – high resolution computed tomography

CPAP – continuous positive airway pressure

PA – pulmonary artery

PTB – pulmonary tuberculosis

SD – standard deviation

BD – broncho dilatation

FVC – forced vital capacity

FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in 1 second

AE – adverse event

SAE – serious adverse event

PA view – posterio-anterior view

PAP – pulmonary artery pressure

INTRODUCTION:

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is not uncommon in different respiratory disorders including OSA(1,2). It affects the QoL adversely. (3) The diagnosis of PH appears greatly restricted in the developing world for lack of RHC as recommended by the guidelines,(4,5) and thus, possibly, a huge number of patients are deprived of the likely beneficial effects of anti PH treatment. Amidst scanty data from the Indian subcontinent, the actual prevalence of PH attending pulmonologists is not negligible. (6) The existing guidelines are not very clear to recommend the medical therapy of class III PH from different causes. Here, we present our initial experience of a real world study of looking at the effect of sildenafil on selected class III PH patients in a pulmonologist's day to day practice without adopting RHC.

METHODS:

The study was performed in a referral pulmonary OPD at Kolkata, India observing a real world protocol been approved by the institutional ethics committee. The method included a) Selection and confirmation of class III PH, b) selection of candidates for anti PH therapy and prescription of sildenafil, and c) observation of the efficacy of treatment in terms of QoL (quality of life) and change in oxygenation (arterial oxygen saturation) with concomitant recording of the adverse and the serious adverse events.

a) Selection and confirmation of PH: The diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension was made at the institute following an indigenous clinic-radio-echocerdigraphic criteria (without doing right heart catheterization).

The diagnostic approach was initiated with suspicion of PH been done from one or more of the following as i) History of dyspnoea, often disproportionately severe, with or without syncope or chest pain, ii) resting low arterial saturation at room air, iii) disproportionate reduction of saturation on exertion with no other obvious explanation, and iv) features of corpulmonale and the cardiac auscultation revealing accentuated second heart sound from pulmonary valve closure with or without pulmonary systolic murmur. The patients were subsequently evaluated with chest x-ray (PA view) and HRCT chest for signs of PH. (7, 8, 9, 10) Once PH-suggestive or PH-specific signs are present these subjects were subjected to doppler and tissue doppler echocardiography following a prescribed protocol by a single echocardiographist. The PH determinant value in echocardiography was the calculated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of ≥ 40 mm of Hg. The echocardiographic exercise included looking for the tricuspid jet velocity (greater than 2.8 m/s) and tricuspid insufficiency pressure gradient (greater than 31 mm mercury) along with measurement of the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPASE), right ventricular outflow tract velocity profiles and different pulmonary flow indices as acceleration time and pre-ejection periods with measurement of tricuspid annular velocity (Tei) and the right ventricular ejection time based on the on this velocity profiles.

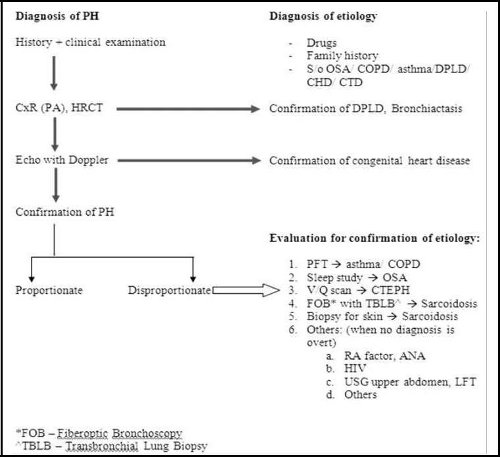

The patients satisfying the clinical, radiological (both x-ray and HRCT chest), and echocardiographic criteria favoring the presence of PH were stamped as having PH and were included for the therapeutic trial. We followed an indigenous algorithm for simultaneous diagnosis of the etiology (figure 1). In case of more than one etiology been present, the predominant one has been noted and in cases where a definite etiological diagnosis cannot be made, the patient had been placed in an etiologically 'indeterminate' group

Figure 1: showing the algorithm been observed by the institute to diagnose PH and determine the etiologies.

b) Selection of the subjects for treatment: The anti-PH therapy was considered after all the subjects were treated adequately for their underlying disease under the given circumstances. The COPD patients were treated with standard COPD pharmacotherapy, home oxygen (whenever indicated), and the best possible rehabilitation measures under the logistic situations. Similarly, the DPLD patients were given treatment as per recommendations with or without home oxygen supplementation and the OSA sufferers were put on CPAP/ auto CPAP therapy. They were considered treatment with sildenafil in addition to the treatment of underlying disease if they continue to show one or more of the following despite the optimal possible treatment of the underlying conditions as (i) a functional status of class III or IV (WHO classification). (11) (ii) poor quality of life with compromised life style, (iii) Baseline resting oxygen saturation <92% at room air in at least two different occasions, and (iv) desaturation ≥ 3% on walking 15 yards or less in the consultation office.

The patients with overt right ventricular failure or functional class IV status with resting saturation being less than 90 percent with PH been quite evident were directly taken up for PH therapy PH therapy with sildenafil with concomitant optimization of the treatment for the etiology with or without advice of hospitalization.

The patients with history of any sure or suspected history of sildenafil toxicity or intolerance or allergy to the agent and the patients on concomitant use of nitroglycerines were excluded. Any patient with pregnancy, lactation, or having any significant systemic disease was excluded from the study at the beginning.

All the patients were discussed about the potential and known side effects of sildenafil and requested to report any suspected or sure side effects while on treatment. Apart, telephonic enquiries were done to all after 15 days of starting the treatment for any intolerance /adverse events. The dose to start with was 10 mg thrice daily and it was hiked to 20 mg thrice a day on tolerance after 3 to 7 days.

c) Observation of the efficacy of treatment: The quality of life was assessed at the initiation and after 12 weeks of treatment in terms of CAT score by a single experienced clinical assistant. The adverse events and the serious adverse events were also recorded.

RESULTS:

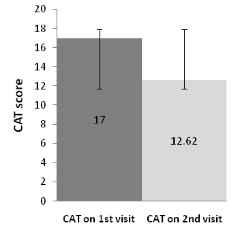

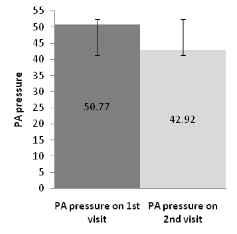

The project was initiated on 2nd week of January, 2013 and by the end of December, 2013, a total of 145 patients were prescribed sildenafil of which 81 patients completed the follow up at 12 weeks after starting the anti PH therapy. Out of the total number, 18 patients dropped out for various reasons (six for headache and seven for pedal edema, three for uneasiness and two for increase in breathlessness). One patient stopped the treatment for unknown reason. 45 of the patients are yet to complete the visit after 12 weeks. The table 1 elaborates the spirometric lung function values, the quality of life in terms of CAT score, the pulmonary artery systolic pressure (in Doppler-echocardiography), the adverse events and other parameters been listed under the common etiological headings. When a patient had more than one possible reason for having PH, the predominant one as per the investigator has been listed. Incidentally, we could get a repeat doppler-echo study been done in 13 patients observing a common protocol by the same echocardiographist; the result showed lowering of PAP concomitant to the lowering of the CAT score (figure 2). None of the patients had any previous exposure to sildenafil.

| |

All |

COPD |

DPLD |

Asthma |

H/o PTB |

OSA |

Miscellaneous* |

Indeterminate |

| No. of |

81 |

29 |

11 |

9 |

17 |

1 |

3 |

11 |

| patients |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age |

62.43 ± |

65.24 ± |

58.36 ± |

63.11 ± |

59.82 ± |

74 |

69.67 ± 2.08 |

59.55 ± 10.21 |

| 10.17 |

7.47 |

8.63 |

14.33 |

12.13 |

| |

|

|

|

| CAT score |

15.33 ± |

15.28 ± |

16.09 ± |

15.56 ± |

14.18 ± |

19 |

15.33 ± 8.08 |

16 ± 4.58 |

| on 1stvisit |

5.52 |

4.5 |

8.1 |

6.46 |

5.57 |

| CAT score |

13.01 ± |

12.83 ± |

13.82 ± |

15 ± 7.05 |

12.29 ± |

11 |

9.33 ± 4.04 |

13.36 ± 5.77 |

| on 2ndvisit |

5.79 |

5.39 |

6.6 |

5.99 |

| p value |

0.004 |

0.03 |

0.23 |

0.43 |

0.17 |

- |

0.12 |

0.15 |

| (change in |

| CAT scores) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Resting |

93.77 ± |

93.56 ± |

89.8 ± |

95 ± 4.36 |

94.73 ± |

|

91 ± 9.64 |

95.36 ± 3.14 |

| saturation on |

95 |

| 1stvisit |

5.88 |

3.82 |

12.36 |

|

4.17 |

|

|

|

| Resting |

94.54 ± |

94.3 ± |

93.09 ± |

95.89 ± |

95.24 ± |

|

|

|

| saturation on |

97 |

94 ± 6.08 |

95.56 ± 3.05 |

| 3.79 |

3.46 |

5.05 |

2.03 |

2.95 |

| 2ndvisit |

|

|

|

| |

|

2.08 ± 2.7 |

1.6 ± 0.67 |

1.9 ± 0.87 |

1.69 ± |

1.88 ± |

1.46 ± 0.61 |

2.24 ± 0.61 |

| FVC(L) and |

|

(57.82 ± |

(55.09 ± |

(66.64 ± |

0.53 |

0.48 |

| |

(61.78 ± 37.81) |

(74.79 ± |

| % |

|

19.98) |

18.95) |

22.87) |

(54.65 ± |

(65.25 ± |

|

12.05) |

| |

|

|

|

|

17.51) |

13.48) |

|

|

| |

|

0.9 ± 0.45 |

1.4 ± 0.52 |

1.24 ± 0.59 |

1.11 ± |

1.26 ± |

1.16 ± 0.5 |

1.77 ± 0.51 |

| FEV1(L) |

|

(37.61 ± |

(59.39 ± |

(55.77 ± |

0.43 |

0.51 |

| |

(62.17 ± 42.33) |

(73.98 ± |

| and % |

|

17.58) |

17.02) |

21.22) |

(44.6 ± |

(57.5 ± |

| |

|

10.63) |

| |

|

|

|

|

16.37) |

26.96) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| %FEV1/FVC |

|

64.63 ± |

110.11 ± |

83.62 ± |

81.62 |

82.75 ± |

98.98 ± 9.67 |

97.44 ± 8.81 |

| |

17.83 |

14.97 |

22.37 |

±22.3 |

34.25 |

| |

|

|

|

| Initial PA |

47.11 ± |

46.66 ± |

47.4 ± |

44.09 ± 5.6 |

47.57 ± |

43.75 ± |

51.24 ± 11.19 |

48.43 ± 12.71 |

| pressure |

8.81 |

10.8 |

9.49 |

9.95 |

4.43 |

| Final PA |

42.92 ± |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pressure |

7.82 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

(n= 13) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AE |

19 |

7 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| SAE |

15 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

* One bronchiectasis and two sarcoidosis

Table 1: The CAT score and the spirometric status (post bronchodilator) of the patients of PH been included for treatment with sildenafil (with. the standard deviation for the applicable parameters have been provided with ± values).

|

(A)

|

(B)

|

Figure 2: Comparison between initial and final CAT score in fig I(a) and pulmonary artery pressure in figure 1(b) of PH patients (n=13) having a repeat echo-doppler study after 12 weeks of treatment with sildenafil.

DISCUSSION:

There have been two important outcomes from the study. The first being that COPD remains the commonest cause of PH (35.8%) to pulmonologist in referral practice and that a wide spectrum of different conditions are responsible for class III PH in our part of the country. Roughly 29 % of the patients etiologically belong to asthma and possibly to suffering from tuberculosis in past together. This remains new as an information as these two conditions are not given a place in the international classification of PH (12). Looking at the lung function, the COPD patients appear to have severe disease (FEV1/FVC = 64.63 and % of FEV1 being 37.61± 17.58) while the asthmatics have relative milder disease (FEV1/FVC = 83.62 and % of FEV1 being 55.77±21.22) suggesting that the chronic asthmatics turning COPD phenotype by lung function are the unlikely members in the list. This makes the story more interesting to look for the pathogenesis of PH in our asthmatics. Roughly 21 % of the patients had history of tuberculosis in the past; this co-incidental finding lead us to separate these patients in a new group; they manifest a restrictive lung function as DPLD having a similar FVC (55 % vs. 55 %) compared to DPLD. Although reported, tuberculosis is also not a well documented and recognized entity to cause PH (13, 14). We could not find out the cause in 13.5 % of cases; surely we missed many conditions as the protocol was some-what restricted for logistic reasons. It is possible that one or more patients in this group belong to PAH.

The second important information derived from out observation is that there has been a universal and statistically significant (p=0.004) improvement in QoL in all the patients as a group. However, the change has been different in PH patients with different etiologies and when seen individually with different number of patients in each subgroup, despite being universal, the improvement is significant statistically only in COPD patients. The drug has been well tolerated with a total of 19 adverse events (AE), 14 hospitalizations from unrelated cause (not related to sildenafil) of which one succumbed. One very sick patient died at home before hospitalization. The common adverse events were pedal swelling, headache, initial increase in the SOB, and uneasiness with vague chest discomfort.

There may be questions about a) diagnosis of PH, b) Indication of therapy, c) dose and choice of the drug, d) The assessment tool. We admit that we had to deviate a lot from the guideline recommendations that included RHC universally for diagnosis. Our argument takes into account the available evidences for the diagnosis of PH from chest x-ray (PA view) and HRCT chest; these evidences have strong specificity for the presence of pulmonary hypertension. (7, 8, 9, 10) this was further supported by echocardiographic diagnosis of PH. Such diagnosis based on clinic-radio-echocardiographic criteria implies that the presence of PH is certain in our patients though the assessment of the exact pulmonary artery pressure is not possible. (15)

The next argument evolves an ethical issue to treat patients without RHC data as no guideline accepts the diagnosis of PH without RHC. To us, withholding the administration of anti-PH therapy cannot be justified any longer especially for people who are sick enough (WHO functional class III or IV) despite the optimum treatment of the underlying conditions. These issues had been discussed at the time of presentation to the Ethics Committee meeting where we could convince the members regarding our stand to remain humane in treating these patients on a defined real world protocol in logistically constraint circumstances when RHC is not available, not possible, or denied by the patients provided the candidates forward a proper informed consent.

There may be questions regarding the duration of optimum therapy for the underlying diseases. We took a cut off value of 2 weeks (except for very sick patients with obvious corpulmonale). To us it appeared that further delay may jeopardize the purpose of such treatment and it also looked unlikely for a patient to show at least the beginning of improvement further on optimum treatment of the underlying condition beyond this period. The next question involved was the treating agent and the dose. We had chosen sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor) as is used widely elsewhere and has been easily available with a relatively low cost in the market. We have kept the dose fixed for comparison; although further hiking the dose in some patients could have yielded a better result. The incorporation of the history of pulmonary tuberculosis in the etiological classification of Class III PH is a new addition in the list of etiologies.

Although tuberculosis has not been officially recognized in the guidelines as a cause of PH, we have shown that these patients form a good bulk (21%) of the PH population in our practice (16) and such patients are also recorded elsewhere.

Regarding assessment of a patient of PH, right heart catheterization and hemodynamic data appear important but are not mandatory as per the guideline recommendations. Tests like six minutes walk test, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, universal repeat echocardiography could have been worthwhile adjuncts to CAT score. Incidentally repeat echocardiography was possible in 13 of our patients concomitant to the repeat recording of CAT score . The observed echocardiographic improvement in terms of the measured PAP (systolic) has been found to go parallel to the improvement in CAT score (figure 2). For logistic reasons we could not measure anything else but CAT score. This is a validated instrument to measure the health status of the COPD patients, (17) and it has also been used in DPLD successfully. (18) Till date, there has been no data available regarding its use in OSA, or other lung conditions causing shortness of breath with jeopardy in lung function. We have chosen CAT for its simplicity, our expertise in using the instrument, and to maintain uniformity in recording the health status in several conditions. The number of patients been observed is small and it is difficult to compare the effect of sildenafil between the different etiological subgroups although it appears from the results that the effect is positive in all the etiological categories.

Despite the weaknesses been mentioned it appears that the treatment of symptomatic class III PH patients with sildenafil remains helpful in terms of improvement in the QoL. Prima face, the proposed clinic-radio-echocardiographic criteria appears acceptable although it needs validation before widespread recommendations. Further studies are urgently warranted in these directions. We feel it necessary for the medical intelligentsia to appreciate and formulate guideline for diagnosis and treatment of class III PH in our country based on the feasibility of investigations in face of resource constraints.

REFERENCE:

1. Seeger W, Adir Y, Barbera J A, Champion H, Coghlan J G, Cottin V, Marco T D, Galie N, Ghio S, Gibbs S, Martinez F J, Semigran M J, Simonneau G, Wells A U, Vachiery J L.

Pulmonary Hypertensionin Chronic Lung Diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D109-16.

2. Arias M A, Garcia-Rio F, Alonso-Fernandez A, Martinez I, Villamor J. Pulmonary hypertension in obstructive sleep apnoes: effects of continuous positive airway pressure. European Heart Journal (2006) 27, 1106-1113.

3. Studer, S M, Migliore, C. Quality of Life in PAH: Qualitative Insights From Patients and Caregivers. Advances in Pulmonary Hypertension. 2012; 10, 4: 222-226.

4. Galie N, Hoeper M M, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery J L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2493–2537.

5. Mc Laughlin V V, Park M H, Rosenson R S, Rubin L J, Tapson V F, Vagre J. ACCP/AHA: 2009 Expert Consensus Document on Pulmonary Hypertension. Jr A. Col Cardiol 2009; 35:14, 1573- 1619

6. Saha D, Bhattacherjee P D, Das S K, Dey R, Ghosh M, Dutta I, Sarma M, Ghosh A, Bhattacharyya PS. Group III Pulmonary Hypertension: relative frequency of different etiologies in a referral pulmonary OPD. Pulmo Face, 2013:13, 3-8 (non indexed journal ISSN no. 2347 – 4823).

7. Kanemoto N, Furuya H, Etoh T, Sasamoto H, and Matsuyama S. Chest roentgenograms in primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest, 1979: 76, 45 – 49

8. Bush A, Gray H, Denison D M. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension from radiographic estimates of pulmonary arterial size. Thorax 1988; 43:127-131.

9. Tan R T, Kuzo R, Goodman L R, Siegel R, Hassler G B, Presberg K W. Utility of CT scan evaluation for predicting pulmonary hypertension in patients with parenchymal lung disease. Medical College of Wisconsin Lung Transplant Group. Chest 1998; 113(5): 1250–1256.

10. Ng C S, Wells A U, Padley S P. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging 1999; 14(4):270–278.

11. Rich S, ed. Executive Summary from the World Symposium on Primary Pulmonary Hypertension; September 6-10, 1998, Evian, France.

12. Simonneau G, Robbins I M, Beghetti, M et.al. Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2009:54, S43-54.

13. Patel V, Khaped K, Solanki B, Patel A, Rathod H, Patel J. Profile of pulmonary hypertension patients coming to civil hospital, Ahmedabad. Int J Res Med. 2013; 2 (1); 94-97.

14. Ahmed A E H, Ibrahim A S and Elshafie S M Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients with Treated Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Analysis of 14 Consecutive Cases. Circulatory, Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine 2011:5 1–5.

15. Hammerstingl C, Schueler R, Bors L, Momcilovic D, Pabst S, et al. (2012) Diagnostic Value of Echocardiography in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Hypertension. PLoS ONE 7(6): e38519. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038519.

16. Bhattacharyya P, Saha D, Bhattacherjee P D, Das S K, Bhattacharyya P P, Dey R. Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Hypertension: the results of a clinical observation. (Manuscript ID: "pvri_3_13". Send it to PVRI Journal as original article).

17. Jones P W, Harding G, Berry P et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648-654.

18. Tachikawa R, Otsuka K, Takeshita J, Tanaka K, Matsumoto T, Monden K. Evaluation of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test for measurement of health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2012 Apr; 17(3):506-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02131.x.

Dr. Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya

Consultant, Institute of Pulmocare and Research, Kolkata

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Rupak Ghosh 1, Saikat Nag 1, Rantu Paul 2, Rana Dey 2 , Ratna Dey 2, Avijit Chowdhury 3 , Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya 1.

1Consultant, 2Research Assistant, Institute of Pulmocare & Research. 3Consultant, West Bengal Liver Foundation (WBLF) .

Abstract

Background: Pulmonary rehabilitation is a cost effective non pharmacological intervention with rewarding effects in allaying symptoms and promoting well being. Such programs are not feasible and virtually not exercised in rural areas of the developing world.

Methods: Multiple single point intensive education on COPD were imparted along with formatted training on major elements of rehabilitation as use of inhalation therapy, respiratory exercise and life style modification etc. on a cohort of rural COPD population in several rural camps at the Birbhum district of West Bengal, India. The changes in the major symptoms (shortness of breath, cough, and wheeze) and the perceptions of the overall health status were measured on visual analogue scale before and 6 weeks after intervention in a group of COPD patients.

Results: There has been a statistically significant improvement (p<0.001) in symptoms and also in the perception of overall health status.

Conclusion: Single point, intensive education and rehabilitation intervention appears significantly effective in rural COPD population in allaying symptoms and improving the perception of the health status over a period of six weeks.

KEY WORDS: COPD, pulmonary rehabilitation, VAS (The Pulmo -Face, 2014; 14:1, 10-14 )

Address of correspondence: Dr. Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya, Institute of Pulmocare and Research, CB- 16, Salt Lake, Kolkata- 700 064, India. Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

ABBREVIATIONS:

6MWT - 6 minute walk test

SGRQ- Saint Georges Respiratory Questionnaire

TDI- Transition dyspnoea index

HRQoL- Health related quality of life

IHD- Ischemic heart disease

VAS- Visual Analogue Scale

PR- Pulmonary rehabilitation

BDI- Baseline dyspnoea index

COPD- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

FVC- Forced vital capacity

FEV1- Forced expiratory volume in one second

INTRODUCTION:

The prevalence of COPD is increasing globally. (1) The dimension is quite significant in India; (2), (3), (4) but information especially from rural background appears scanty. (5) In our experience, 12.18 % of total OPD turnover has been from COPD. (6) Most of the time, pharmacotherapy remains the sole management of the disease for several Logistic constraints. Therefore, COPD rehabilitation has not been practiced formally except for limited urban hospitals and published data is yet to be available regarding the Indian experience.

The situation in the rural areas is likely to be even worse for several reasons as lack of education and awareness, economic constraints, lack of access to modern health care, and different other geo-socio-cultural reasons. Scanty data is available regarding our rural COPD patients (5) and there is hardly any information regarding any effort of non pharmacological interventions in them.

Since it is not possible to adopt a formal COPD rehabilitation that requires a lot of organizational input and economic commitments, we decided to make a single point intervention of education and training based on a simple curriculum. This was prepared with our background experience of teaching COPD patients attending our OPDs and training camps incorporating the basic issues as proper inhalation technique, breathing exercise, walking, nutrition etc. On a follow up visit after 6 weeks of such intervention we assessed the situation based on visual analogue scale (VAS).

METHODS AND MATERIALS:

Inclusion criteria: Patients of either sex aged more than 40 years with or without history of active smoking but with history of progressive shortness of breath, cough and/or expectoration for over 2 years were screened for presence of COPD. Those who show feature of airflow limitations ( FEV1/FVC < 70 %, and FEV1 < 70 %) without reversibility (less than 10 % increment of peak expiratory flow rate after 20 minutes of 4 puffs of salbutamol with a spacer) were regarded as cases of COPD.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with recurrent purulent expectoration, clinically detected clubbing/ cyanosis or any skeletal deformity, known or suspected ischemic heart disease, congenital or valvular heart disease apparent in clinical examination, any other significant pulmonary or cardiac problem apparent from the chest x-ray (done on clinical suspicion), or having any known co-morbidity of significant dimension, were excluded from the study. Very sick patients, those unable to perform spirometry or unwilling to give consent were also excluded.

The whole work has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee before starting.

The effort essentially involved three components as (A) formatting a one day COPD education and training course effectively, (B) reaching and ensuring the co-operation and compliance of the rural COPD patients and, (C) actually performing the job

A) The past experience of doing several COPD education and training camps with publication of a booklet as a part of our institutional activities helped us a lot to formulate, print and publish a simple curriculum in Bengali (with pictures describing several exercises and inhalation devices and their uses) apt for the population to address and also to plan the actual course of action foreseeing the planned camps. The curriculum also provides a review of what to do and what not to do for the patients. It includes practical and essential elements on areas as a) about the disease with role of smoking in its pathogenesis, b) when to suspect and diagnose COPD, c) what happens in COPD to the lungs and what are the symptoms, d) what a patient of COPD should know, e) how to use inhalers, f) required life style modifications as smoking cessation, exercise, proper food, avoidance of smoke and irritants, and use of oxygen when required.

We experimented the booklet in our conventional COPD camps and became confident and apt in using it to a gathering of patients with or without audio visual assistance.

B) Reaching to the target population was possible through the infrastructure and man power help of an organization (West Bengal Liver Foundation) engaged in rural based epidemiological work and the involvement of our consultant working in Rural Bengal, Suri, Birbhum. Ten volunteers, chosen from the WBLF, were trained beforehand to suspecting COPD patients in villages based on appropriate response to a set of simple questions (not yet validated) and bring them (about ten patients each) to the camps at 8.30 A.M. and 9.00 A.M. in summer and winter time respectively.

C) Actually performing the job: a) fixing a venue: mostly the municipality building or school (in weekends) where a big room being fixed for common address, b) making provision for spirometry with three spirometers and Indian Chest Society certified trained technicians, c) joining our rural consultants with two doctors and two trainers from our head quartersto accomplish the physical examination and education.

The modus operandi has been discussed and decided in the evening before the program. A program line has been followed with different points as

1) Welcome and registrations : White desk

2) Filling up the basic data : Black desk -here we fill up some basic facts including symptoms and keep a record on VAS on shortness of breath, cough, wheeze, and overall health status being perceived by each patient.

3) Spirometry : Green desk

4) Clinical examination and prescription : Blue desk

The movement of the patients has been shown in Fig 1

Individual members were entrusted with their role and small mock exercise is performed for the camps.

5) Once the clinical examination is over, the participants were addressed on our formatted education program in a common gathering with some questions and answers.

In the same, use of inhalers and respiratory exercise (diaphragmatic breathing and breathing with positive expiratory pressure – 'pursed leap') are demonstrated. One or two patients are usually selected randomly to repeat the procedure so to ensure the attention of the audience to register the issues in their minds. Free questions regarding the disease, the treatment and the demonstrated exercises were allowed thereafter.

6) Following that the team gets divided into 3 groups to check inhalation technique in one to one fashion and re-educate on breathing exercise. We used only DPI (with lupihaler, Lupin Pharma) for the purpose.

7) Drug distribution: We arranged for 15 days course of DPI for all the patients who attended and needed the drug. The travel cost was also reimbursed at this point.

8) It was followed by tea and a food packet. They were told to revisit us after 6 weeks on a fixed date.

FOLLOW UP:

The patients were followed up after 6 weeks in another subsequent camp when we arrange a rehearsal of inhalation, exercise and education on a common gathering along with rectifying flaws, if any in the techniques. The impression of symptoms as shortness of breath, cough, wheeze and overall health status being perceived by each patient were all recorded on VAS.

RESULTS:

The pooled data from three such camps were collected for analysis. A total of 175 patients attended the camps before compilation of data. Out of them 40 patients were excluded for several reasons [6 had severe dyspnoea, 4 had active hemoptysis, 3 had suspected / proved active tuberculosis (carrying RNTCP record), 1 had features of moderate pleural effusion, 8 could not perform spirometry, 4 showed reversibility in spirometry, 2 had normal spirometry, and 12 had findings suggesting clinically significant some other diseases]. The patients with active problems were referred to the local/ district Govt. Hospitals. Thus, 135 patients were finally diagnosed COAD and all of them agreed to undergo the study and to mark their symptoms on VAS. However, 90 out of 135 did not come for follow up after 6 weeks. Hence, only 45 patients were incorporated for the final analysis.

The mean age of the patients included for analysis was 56.58 ± 9.65 years with the sex ratio (male: female) was 3.2: 1.3. The mean duration of shortness of breath, cough, and wheeze were 5.66±3.46, 4.62±3.70, and 4.73±3.79 years respectively. All male patients (32 of 45) were either active or ex smokers while the female subjects too were ex-smokers (n=11) or passive smokers (n=2). Very few patients were aware about their co-morbidities (hypertension in one, diabetes in one, is chemic heart disease in two). Six patients had the history of hospitalization due to shortness of breath or suspected pneumonia. The mean BMI was as low as 16.73 ± 3.17; speaking about the poor nutritional status of the selected participants. Spirometric data analysis showed the mean FVC, mean FEV1 and the mean FEV1/FVC ratio to be 1.34 ± 0.67 litres, 0.88 ± 0.47 litres and 67.53 ± 17.97 % respectively.

The change in the VAS scoring has been found significant (p< 0.001) for all the symptoms and the overall perceived well being (see table 1).

Table 1: Mean scoring on VAS of symptoms and perceived well being

| Parameters |

1st visit |

Follow up visit (after 6 weeks) |

p-value |

| Shortness of breath (n=45) |

38.67 ± 13.20 |

60.22 ± 24.14 |

<0.001* |

| Cough (n=45) |

39.44 ± 13.54 |

58.56 ± 24.65 |

<0.001* |

| Wheeze (n=43) |

42.09 ± 14.53 |

58.26 ± 21.38 |

<0.001* |

| Overall health status (n=45) |

37.56 ± 11.11 |

58.56 ± 22.07 |

<0.001* |

* statistically significant

The table 1 shows the change in symptoms and the perceived sense of wellbeing before and after 6 weeks of intervention. There has been a significant improvement in visual analogue scale in all the parameters.

DISCUSSION:

COPD is a global and increasing public health problem. (1, 7) In India, the dimension is quite huge (2, 3, 4) with significant prevalence of COPD in rural areas. (5) COPD rehabilitation is a definite effective non pharmacological intervention. (8, 9) While the data from the developing world regarding the epidemiology of COPD is scanty, that regarding the COPD rehabilitation in rural areas of the developing world is hardly available. The reason being manifold; the rural areas of the developing world are frequently burdened with poverty, overpopulation, geo-socio-political adversities, lack of education and awareness with lack of access to proper health care. Therefore, many a times, the patients seek medical attention late in advanced stage and it appears not possible to implement the structured organized interventions of formal COPD rehabilitation programs in rural India.

Since the burden of COPD is so huge (2, 3) and the evidence in favor of rehabilitation is so strong (9, 10, 11, 12) that despite the adverse ground realities, there should be efforts for best possible rehabilitation of these patients. Significant clinical and statistical improvement in basal dyspnoea and quality of life has been seen with simple home-based exercise training programs using the shuttle walking test. (13) Even a simple outpatient-based pulmonary rehabilitation program can improve the exercise endurance, quality of life, and reduce dyspnoea scale and hospital utilization with reduction in the health care cost. (14) The worthwhile benefit of out-patient rehabilitation program can persist for a period of 2 years in terms of significant reduction in exacerbations, improvement in perception of dyspnoea, and HRQoL. (15) Home based rehabilitation program has also been found comparable to hospital based program. (16) Duration wiser, even a shortened 4-week supervised pulmonary rehabilitation program is as effective as a 7-week supervised programme at the comparable time points of 7 weeks and 6 months. (17)

So it appears that any intervention for rehabilitation should, perhaps, be better than none. Hence, we decided to try a single point structured and organized intervention for COPD education and training for self managed care and rehabilitation in rural areas on a curriculum covering the major important issues related to the disease in simple question-answer forms. The area of operation and the manpower support were thoughtfully selected in collaboration with the West Bengal Liver Foundation. Finally, a structured modus operandi was prepared through repeated discussions and interactions amongst the working members keeping the logistics and expected practical problems in view. Perhaps, the key to success of such a program has been the appropriate training and mobilization of the manpower concerned according to the perceived scenario.

Visual analogue scale has been in use to assess several disease entities; the beauty being its simplicity to use. Conducted to see the relative power of outcome measurements of COPD rehabilitation program between the most frequently used and validated variables as exercise performance, dyspnoea, and health-related quality along with VAS in a population of patients with severe COPD qualifying for lung volume reduction surgery, a trial revealed that the VAS at peak exercise, BDI/TDI, and CRQ adequately reflect the beneficial effects of pulmonary rehabilitation and all of them correlate well with each other (18). Due to their simplicity and sensitivity, VAS at peak exercise, 6MWT, and CRQ may be the best practical tools to evaluate responsiveness to PR. (18) Although the sensitivity of the VAS to bronchodilation has been found to be better in asthmatics than in COPD subjects, (19) we choose to see the effects on VAS alone although concomitant assessment with other valid parameters like SGRQ, 6MWT, BDI/TDI, etc could have been better. Using VAS happened to be the most feasible option to assess the changes in symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, wheeze) and the subjective perception of the overall health status for such single point intervention in rural COPD population.

COPD rehabilitation in rural areas is not new and people, so far, have tried to replicate the formal evidence based COPD rehabilitation program in rural areas. (20) Effort intensive program at the primary care with implementation of evidence based guidelines have found to have a significant positive impact in several parameters as HRQoL, health status, changes in practice behaviour, improvement in smoking cessation and healthcare utilization. (20) It has also been found to reduce effectively the health care cost in rural areas. (21)

In our study, we had to adopt a deviation in confirming COPD by lung function. For obvious pragmatic reason we had to resort to post bronchodilator PEFR measurement and we kept a PEFR change of 10% to exclude the diagnosis of asthma. The criteria, certainly, appear stringent. Doing post bronchodilator FEV1 was not possible by us in one day camp set ups and form the initial flow volume loop and the FEV1 value (0.88 ± 0.47 liters) along with lack of reversibility in PEFR, we are fairly sure to have no asthma patient included in our list. However, we cannot rule out the inclusion one or two patients of chronic asthma with remodeling and loss of reversibility to bronchodilators.

The impressive change in all the parameters concerned as shortness of breath, cough, wheeze, and overall health status perceived by the patients (p< 0.001) signifies the impact of such one point simple, feasible but intensive intervention along with the pharmacotherapy in our rural COPD sufferers. Some additional interventions as supply of the full course of medication, monitoring by the rural volunteers, and applying rewards for smoking cessation and adherence to the exercise and proper inhalation etc. could have helped more. All the subjects attending the COPD education and training camps were economically constrained people. A systematic record with a much higher number of recruits with analysis of the impact of several factors as monthly income, family status, educational status etc. could have been definitely better to provide an insight regarding their compounding effects on the intervention. Moreover, we did not incorporate an organized smoking cessation program and we have not analyzed the effects of such intervention on smoking cessation. We have no idea about the existing treatment for their disease and the positive change may also be partly contributed by pharmacotherapy with the training and education; it is not possible to isolate the impact of the two from the results. A concomitant control group with pharmacotherapy alone could have been a useful adjunct.

In conclusion, it appears that a little organized and intensive effort of education and training alone with pharmacotherapy can bring forth significant positive changes in the suffering of our COPD boors through self-managed rehabilitation efforts. Further research should be done to identify separately the positive impact of education and training and finally formulate and validate an alternative but easy, effective, and feasible rehabilitation program for rural COPD patients. This will probably mean a great change in the saving health and improving quality of life in our rural population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS :

1) Acknowledgments section that describes the role of each author in the preparation of the manuscript.

2) West Bengal Liver Foundation for allowing the irvolunteers to work for us

3) Lupin laboratories for providing us with spirometers and helping manpower

ACCP : for offering the chest foundation award to us; although the fund was not meant for research, the actual job would not have been possible without the help of the award money.

REFERENCE:

1. Klaus F R, Suzanne H, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis,Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: GOLD Executive Summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007; 176:532-555. Updated consensus guildelines for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD.

2. Jindal S K, Aggarwal A N, Gupta D. A review of population studies from India to estimate national burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its association with smoking. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2001; 43:139-147.

3. Jindal S K, Aggarwal A N, Chaudhry K, Chhabra S K, D'Souza G A, Gupta D, et al. Asthma Epidemiology Study Group. A multicentric study on epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its relationship with tobacco smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006; 48:23-29.

4. Jindal SK. Emergence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an epidemic in India. Indian J Med Res. 124, December 2006, pp 619-630

5. Mahesh P A, Jayaraj B S, Prahlad T, Chaya S K, Pravakar A K, Agarwal A N, Jindal S K. Validation of structures questionnaire for COPD and prevalence of COPD in rural areas of Mysore: A pilot study. Lung India. 2009;26:63-69

6. Dasgupta A, Bagchi A, Nag S, Bardhan S, Bhattacharyya P S. Profile of the respiratory problems in patients presenting to a referral pulmonary clinic. Lung India. 2008; 25: 4-7.

7. Murray C J, Lopez A D .Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997; 349:1498-1504.

8. Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson T J, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003793. DOI: 10.1002 / 14651858. CD003793.pub2

9. Ries A L, Bauldoff G S, Casaburi R, Mahler D A, Rochester C L, Herrerias C . Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Joint ACCP/AACVPR Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines Chest. 2007;131:4S–42S

10. Goldstein R, Gork E, Stubbing D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of respiratory rehabilitation. Lancet. 1994; 344: 1394–1397.

11. Guell R, Casan P, Belda J, et al. Long term effects of out patient rehabilitation of COPD . Chest . 2000;117:976–983

12. Lacasse Y, Wong E, Guyatt G H, et al. Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 1996;348:1115–1119

13. Herna´ndez M T E, Rubio T M, Ruiz F O, Riera H S, Gil R S, and Go´mez J C, Results of a Home-Based Training Program for Patients With COPD. Chest. 2000;118:106–114

14. Hui K P, and Hewitt A B. A Simple Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program Improves Health Outcomes and Reduces Hospital Utilization in Patients with COPD. Chest. 2003;124:94-97

15. Gu¨ ell R, Casan P, Belda J, Sangenis M, Morante F, Guyatt G H, and Sanchis J. Long-term Effects of Outpatient Rehabilitation of COPD:A Randomized Trial. Chest. 2000;117:976–983

16. Strijbos J H, Postma D S, Altena Richard van, Gimeno F, and Koeter G K. Hospital-Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program and a Home-Care Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program in Patients With COPD: A Follow-up of 18 Months. Chest. 1996;109:366-72

17. Sewell L, Singh S J, Williams J E A, Collier R, Morgan M D L. How long should outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation be? A randomised controlled trial of 4 weeks versus 7 weeks. Thorax. 2006;61:767-771

18. de Torres J P, Pinto-Plata V, Ingenito E, Bagley P, Gray A, Berger R, and Celli B. Power of Outcome Measurements to Detect Clinically Significant Changes in Pulmonary Rehabilitation of Patients With COPD. Chest. 2002; 121:1092–1098.

19. Noseda A, Schmerber J, Prigogine T, and Yernault JC. Perceived effect on shortness of breath of an acute inhalation of saline or terbutaline: variability and sensitivity of a visual analogue scale in patients with asthma or COPD.EurRespir J. 1992;5:1043-1053

20. Deprez R D, Kinner A, Baggott L A, Milard P, Moody B. Rural COPD quality improvement initiative. APHA scientific session, Nov 7, 2007, abstract # 158397.

21. Rasekaba T M. Can a chronic disease management pulmonary rehabilitation program for COPD reduce acute rural hospital utilization? Chronic Respiratory Disease. 2009; 6(3):157-163.

Dr. Parthasarathi Bhattacharyya

Consultant, Institute of Pulmocare and Research, Kolkata

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.