Basanta Hazarika 1, Suresh Sharma 2, Jogesh Sharma 3, Kripesh Sharma 4, Nita Basumatary 2, Sushmita Choudhury 5

1Associate Professor, 2 Resident Physician, 3 Professor, 4 Assistant Professor Pulmonary Medicine, 5 Registrar Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam,India

Abstract

Zygomycosis, life-threatening fungal infection, almost essentially affects immune-compromised hosts. Here we report and discuss an uncommon presentation of zygomycosis as mediastinal mass with systemic symptoms in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes.

KEY WORDS: zygomycosis, mediastinal mass, immunocompromised host, posaconazole (The Pulmo -Face, 2014; 14:1, 22-23 )

Address of correspondence: Dr. Basanta Hazarika, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Guwahati Medical College, Guwahati- 781023, Assam, India. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

INTRODUCTION

The Zygomyces or Mucor class of fungi comprised of the orders Mucorales and Entomophthorales. While the Entomophthorales rarely causes subcutaneous and mucocutaneous infections in immunocompetent hosts in developing countries, (1) the Mucorales, a histologically distinct order, are commonly associated with the invasive, disseminated and fatal forms of mucormycosis affecting immunocompromised patients across the world.(2) A rare case of zygomycosis presenting as a mediastinal mass obstructing right main bronchus is detailed below.

THE CASE DETAILS

A 62 year old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to the out-patient Department of Pulmonary Medicine of Guwahati Medical College with moderate fever for 3 months associated with dry and troubling bouts of cough continuing despite therapy. After about a month of the onset of his illness, he developed shortness of breath and he was put on anti-tubercular therapy on radiological suspicion to which he did not show any response.

On physical examination, he had tachycardia (pulse rate of 112/minute), fever (axillary temperature 102.8°F), with a blood pressure of 96/66 mm Hg and respiratory rate of 24 per minute. The respiratory system examination revealed dullness on percussion with reduced breath sound and occasional crepitations on the right side while his cardiovascular, abdominal and nervous systems examinations were within normal limits. The chest x-ray film revealed irregular opacities in the right lower lobe. Laboratory investigations revealed microcytic anemia (Hemoglobin of 9.0 grams/ dl), poorly controlled diabetic status (Fasting and post-prandial blood sugar as 382 and 406 mg/dl respectively with HbA1C being 14%), impaired renal function (creatinine level as 3.8 mg/dl, urea- 80 mg/dl), and normal liver function tests. Urinalysis revealed 3+ sugar with no protein, pus cells or casts been detected. The patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and insulin.

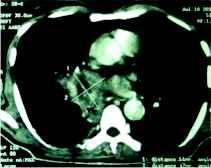

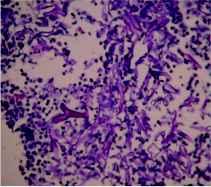

After 10 days of treatment, patient's diabetes was controlled but high grade fever and dyspnoea persisted. CT thorax was done which revealed necrotic soft tissue mediastinal mass measuring 5.1×4.7 cm in the right parahilar location (figure 1) closely encasing the bronchus intermedius and right inferior pulmonary vein. Few necrotic nodes abutting the primary mass lesion were also noted. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed obstruction of right main bronchus with soft tissue with mucosal hyperemia. The material aspirated through trans-bronchial needle aspiration displayed non-septate fungal hyphae suggestive of zygomycosis on smear examination (figure 2).

Figure 1: Coronal section of CT thorax (mediastinal window) shows a big mass (5.1×4.7 cm) in right parahilar mediastinum. The outline of the mass is fairly regular with occasional spiky projections and an area of liquefaction (necrosis) is seen within at the center.

Figure 2: The hematoxilin-eosin stain of the aspirate reveals broad, irregular, nonseptate, right-angled, branching hyphae of zygomyces (see arrow) against an eosinophilic and inflammatory background in the transbronchial aspirate smear.

Once the diagnosis was made, considering his impaired renal function and the financial status, he was put on posaconazole in the dose of 200 mg 12 hourly with concomitant monitoring of blood counts, liver and renal function tests. The patient responded dramatically and his fever subsided after 4th day with reduction of dyspnoea and return of the physical well being. He was discharged on posaconazole 200 mg 12 hourly. Repeat CT scan of the thorax after 3 weeks of therapy revealed mark resolution of the lesions (figure 3).

Figure 3: A repeat CT cut at the same area reveals significant resolution of the mass lesion after treatment with posaconazole.

DISCUSSION

Zygomycosis constitutes the third most common cause of invasive fungal infection after Aspergillus sp. and Candida sp. Inhalation of the spores from the environment is thought to be the primary mode of transmission of mucormycosis, (3) the commonest zygomycoses, with the lungs being the second commonest site of infection. (4) Mucormycosis characteristically affects immunologically compromised hosts, with the rhinocerebral form occurring most commonly in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (2) and pulmonary mucormycosis in leukaemia and lymphoma. (5) However, pulmonary and cutaneous involvement has been reported in apparently healthy individuals as well. (6) Patients with Diabetes Mellitus are more predisposed to invasive mucormycosis because of the impaired neutrophilic function. Furthermore, the acidosis and hyperglycemia present in diabetes provides an excellent environment for the fungus to grow. (9) Based on clinical presentation and the involvement of a particular anatomic site, mucormycosis can be divided into at least six clinical categories: (i) Rhinocerebral, (ii) Pulmonary, (iii) Cutaneous, (iv) Gastrointestinal, (v) Disseminated, and (iv) Miscellaneous such as mediastinal mucormycosis.

Mediastinal mucormycosis or zygomycosis is a rare entity and has been presented as case reports (6,10-12). It may occur secondary to the spread from the pulmonary disease. The clinical presentation may vary depending on the mediastinal structures involved and a patient may present with features of mediastinitis or obstruction of superior vena cava. The diagnosis is based on the histological demonstration of broad, irregular, nonseptate, right-angled, branching hyphae by hematoxylin and eosin and specialized fungal stains. (13) Culture of the organism from body fluids is successful in fewer than 20% of cases. (2) A positive culture helps in further differentiating the various sub-species. In absence of culture confirmation in our case, though likely, we cannot stamp it as 'Mucormycosis' since Mucor, Absidia and Rhizopus are the three important genera under Zygomyces and all of them show aseptate hyphae or scarcely septate hyphae on histopathological or cytopathological examination.

Surgical debridement along with antifungal therapy remains the mainstay of treatment of zygomycosis; (14) the amphotericin B being regarded as the first-line antifungal therapy. Serial monitoring of renal function has been essential in treatment with amphotericin-B and liposomal form of the drug is recommended in cases of compromised renal function or in co-prescription of other nephrotoxic agents or in patients been otherwise intolerant to amphotericin-B. Posaconazole, a second-generation triazole agent, has been found high potency both in vitro and in vivo activity against some zygomycosis Mucormycosis. This drug has frequently been used as a salvage regimen in refractory cases in patients intolerant to amphotericin-B. (15) Delays in instituting therapy may be associated with increased mortality. Simultaneous treatment of predisposing factors as hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and neutropenia is critical.

CONCLUSION

Mediastinal zygomycosis (possibly mucormycosis), a rare form of the disease, may be a rare presentation in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or an immune-compromised state. Timely administration of appropriate antifungal therapy may save the patients.

REFERENCE

1. Herstoff JK, Bogaars H, Mcdonald CJ. Rhinophycomycosis Entomophthoras. Arch Dermatol 1978; 114:1674-1678.

2. Lehrer RI, Howard DH, Syperd PS, Edwards JE, Segal GP, Winston DJ. Mucormycosis. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93:93-108.

3. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ: Mucormycosis in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13:236-301.

4. Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1986; 65:113-123.

5. Meyer RD, Rosen P, Armstrong D. Phycomycosis complicating leukemia and lymphoma. Ann Intern Med 1972; 77:871-879

6. Eckert HL, Khoury GH, Pore RS, Gilbert EF, Gaskell JR. Deep Entomophthora phycomycotic infection reported for the first time in the United States. Chest 1972; 61: 392-394.

7. Butala A, Shah B, Cho YT, Schmidt MF. Isolated pulmonary mucormycosis in an apparently normal host: a case report. J Natl Med Assoc 1995; 87:572-574.

8. Matsushima T, Soejima R, Nakashima T. Solitary pulmonary nodule caused by phycomycosis in a patient without obvious predisposing factors. Thorax 1980; 35:877-878.

9. Chinn RY, Diamond RD. Generation of chemotactic factors by Rhizopus oryzae in the presence and absence of serum: relationship to hyphal damage mediated by human neutrophils and effects of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. Infect Immun 1982; 38:1123–1129.

10. Leong AS. Granulomatous mediastinitis due to rhizopus species. Am J Clin Pathol 1978; 70:103-107.

11. Connor BA, Anderson RI, Smith JW. Mucor mediastinitis. Chest 1979; 75:525-526.

12. Marwaha RK, Banerjee AK, Thapa BR, Agrawal SM. Mediastinal mcormycosis. Postgrat Med J 1985; 61:733-735.

13. Lass-Florl C. Mcormycosis: conventional laboratory diagnosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15:60-65.

14. Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, Hegde SS, Tedder SD, Lowe JE: Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 57:1044-1050.

15. Tobon AM, Arango M, Fernandez D, Restrepo A. Mucormycosis (mcormycosis) in a heart-kidney transplant recipient: recovery after posaconazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 36:1488-1491.

Dr. Basanta Hazarika,

Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Guwahati Medical College,

Guwahati- 781023, Assam, India.

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

1 Post graduate trainee, 2 Consultant, Department of Medicine, BR Singh Hospital and Centre for medical education and research, Eastern Railways, Kolkata

Abstract

A 54 years old patient of long standing asthma had worsened with relative steroid dependence without any obvious reason. He revealed raised IgE (< 1000 kU/L,) but evidence to sensitization to fungi including aspergillus. A treatment with itraconazole reduced symptoms and made the tapering of the steroid dose possible.

KEY WORDS: aspergillosis, itraconazole, IgE, asthma, fungal sensitization (The Pulmo -Face, 2014; 14:1, 24-25 )

Address of correspondence: Dr. Angira Dasgupta, Department of Medicine, BR Singh Hospital and Centre for medical education and research, Eastern Railways, Kolkata, Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of severe asthma is a challenge. In recent years, a lot of interest has been generated around allergic fungal airway diseases like allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA). Infact, a new asthma variant has been described by Denning et al and this has been called "severe asthma with fungal sensitization (SAFS)". (1) The epidemiology of this entity remains unknown. But the importance of identifying this variant of severe asthma is related to treatment implications whereby additional antifungals may be beneficial. (2) We describe here a patient of severe asthma with fungal sensitization whom we treated with an antifungal agent in addition to the usual guideline based strategy including omalizumab.

THE CASE

A 54 year old gentleman who has been diagnosed as asthma from the age of 14 years presented with blood streaked sputum for 5 days. His asthma had gone worse in the past 2 to 3 years when he required at least 3 short courses of oral corticosteroids in a year in addition to high dose inhaled corticosteroids (fluticasone propionate 1000 mcg daily) and long acting bronchodilators (salmeterol 50 mcg daily). He is a never smoker and denied any history suggestive of any nasal, sinus, gastroesophageal, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases. Earlier his asthma used to remain well controlled with high dose combination inhalers only. He worked as a site inspector for the railways and used personal protective equipment at work.

On examination he had bilateral diffuse polyphonicrhonchi. His spirometry showed very severe but reversible airflow obstruction FEV1 (0.83 L, 30% of predicted; FVC 1.3 L, 38% of predicted; FEV1/FVC 0.63). His routine blood examination was normal. He did not have peripheral eosinophilia. But his serum IgE was 573 IU/l. Specific fungal IgE was raised for Aspergillous fumigatus, Mucor racemosus, Candida Albican and dermatophagoides. CT scan of chest showed bronchiectasis in both upper and lower lobes of both lungs with mucous impaction and air fluid level in a cystic bronchiectatic cavity in right lower lobe (Figure1).

Figure 1: HRCT scan of chest showing bronchiectasis with mucous impaction and air fluid level in a cystic bronchiectatic cavity.

He was treated with oral corticosteroids and antibiotics in addition to high dose combination inhaler. His minimal steroid requirement was 15mg daily below which he started wheezing and got limited in his daily activities. He was started on injection Omalizumab (300mg twice a week) according to GINA guidelines and as oral steroids were being tapered he again started to get wheeze with mucoid expectoration and got limited in his activities of daily living at a dose of 10 mg prednisolone. He was then treated with itraconazole (200mg twice a day) in addition to the other medications.

This caused considerable improvement in his functional status although spirometry did not show any significant improvement. His oral steroid dose could now be tapered off to 5 mg without any exacerbations in 6 months. He continues to remain in follow up.

DISCUSSION

This case report demonstrates a typical case of severe atopic asthma who was later diagnosed as having "severe asthma with fungal sensitization". This patient continued to require high doses of oral corticosteroids despite guideline based therapy and was ultimately treated with additional itraconazole which led to improvement in his functional status with successful reduction in the dose of oral corticosteroids. "Severe asthma with fungal sensitization" or SAFS is a fairly recent nomenclature. These patients have severe asthma and are sensitized to one or more fungi, but have normal or only slightly elevated total IgE concentrations. The clinical and diagnostic manifestations of SAFS are thought to arise from an allergic response to multiple antigens expressed by A. fumigatus and possibly other fungi, colonizing the bronchial mucus. The published criteria for the diagnosis of SAFS are (i) severe asthma, (ii) total IgE < 1000 kU/L, and (iii) positive skin test or raised specific IgE to any fungus. (1) Some authors consider SAFS as a precursor of ABPA although this remains to be established. (3)

Itraconazole has been investigated for its use in SAFS in the recently published Fungal Asthma Sensitization Trial (FAST) which showed only modest improvements in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ). (2) The mechanism of the efficacy of azole and its duration of use in SAFS is still unclear. It has been suggested that treatment with itraconazole decrease airway colonization and thereby halt the resulting immune responses. Further, itraconazole increases the levels of certain inhaled steroids, thereby potentiating the effect of steroids. (4,5) However, the effects of itraconazole in the above trial lasted only for the duration for which it was administered.

This patient continues to be on high dose inhaled corticosteroids, 5mg of oral prednisolone and bimonthly Omalizumab injections for 6 months without significant exacerbations and a stable exercise capacity. We had discontinued itraconazole after 4 months.

CONCLUSION

The entity "severe asthma with fungal sensitization" needs further investigation. Its epidemiology, natural course and exact place in severe asthma guidelines remains unclear. Further randomised controlled trials with good power are needed to establish treatment strategies of this variant of severe asthma.

REFERENCE

1. Denning D W, O'Driscoll B R, Hogaboam C M, Bowyer P, Niven R M. The link between fungi and severe asthma: a summary of the evidence. Eur Respir J 2006; 27(3):615–626.

2. Denning D W, O'Driscoll B R, Powell G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of oral antifungal treatment for severe asthma with fungal sensitization: The Fungal Asthma Sensitization Trial (FAST) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:11–8.

3. Agarwal R. Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitization. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep.2011; 11:403–413.

4. Varis T, Kaukonen K M, Kivisto K T, et al. Plasma concentrations and effects of oral methylprednisolone are considerably increased by itraconazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:363–8.

5.Varis T, Kivisto K T, Neuvonen P J. The effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral prednisolone. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000; 56:57–60.

Dr. Angira Dasgupta

Department of Medicine, BR Singh Hospital and Centre for medical education and research,

Eastern Railways, Kolkata

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.